By Nora Hickey

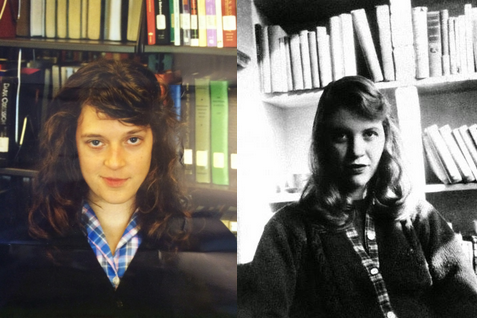

By Nora HickeyDuring my senior year in college, I was obsessed with Sylvia Plath. At my small, liberal arts, verdant Michigan school, all seniors had to design and implement an “individualized project” that had some connection to our major. I had stumbled upon literature after my dreams of working with dolphins were crushed by poor biology grades and my quick realization that words were as powerful as a laboratory. And, during senior year, I discovered Plath—a commanding wordsmith with a salacious backstory to boot. She quickly became the focus of my senior project, and books by and about Plath soon piled up in my room. I started using her journals (beautifully, rawly presented unabridged) as a sort of daily talisman—I would open the book at random, point to a line, and let this guide me through the day. One of my friends’ senior projects involved photographing her friends in a staged photo that replicated a picture of an influential person. I chose a snapshot of Smith College–era Sylvia Plath, her hair long and her face wry. For spring break, my mom and I drove to Indiana University where her juvenilia was kept in a sun-filled, spacious library. That year, as I drank shitty beer from kegs and showered less frequently than I should have, Plath was in my ear. I brought her up in conversations, wanted people to see her brilliance, her “blood jet!” The secret was, though, that I wasn’t sure I understood what was happening in her poetry myself. I was in love with her language, yes, because it rang out in such vivid pain that I couldn’t ignore it. But I was also captivated by her life story—the depression, the suicide attempts, the electroshock therapy. I cranked out a thirty-page paper on her poetry in relation to her husband’s, the poet Ted Hughes—poems about her—and the committee passed it. I think it’s somewhere in an old brick house in Kalamazoo, collecting dead flies and dust. I didn’t know that I would keep writing poetry back then, but ten years later, I’m still at it, still prodding language from bodies and land, from beauty and brutality. I still visit Plath, but with less of my sensation-seeking young eyes, and her poetry continues to mark me, but in a different way. This time, I am awed by her drive, talent, cunning, and vision, her abilities as a poet. “If my mouth could marry a hurt like that,” she asks of the vibrant flower in “Poppies in July,” and I know, I will wed her words over and over.

No comments:

Post a Comment